*** Johnson County Investigates Toxic Chemical Spread, Calls for Immediate Change in Biosolids Application, Regulation ***

The sun had already set, and Larry Woolley was at home in Cleburne on this winter night in December 2023.

Having served as a Johnson County Commissioner since 2015, Woolley had already experienced the 24/7 nature of the job. So, when the phone rang after office hours, Woolley wasn’t surprised to hear the voice of a concerned citizen. Actually, the word “concerned” is too tame – too antiseptic – to describe the reason for this particular call, placed by Tony Coleman, a Johnson County rancher whose 300-plus acres sit just outside of Grandview in Woolley’s precinct.

Coleman was contacting Woolley to let him know about a stillborn heifer. Woolley hung up and quickly called a veterinarian to ask how to best preserve the body.

“Place the body in a bag, and then bury the bag in ice,” Woolley was told. He relayed the information to Coleman and said he would be there first thing Monday morning to pick up the animal.

Why would a County Commissioner become involved in this scenario? It would make more sense if the call was connected to Woolley’s personal history: Bachelor of Science in Agriculture Education. Former vocational ag teacher. Fellow lifelong rancher. However, on this particular night, Coleman’s call to Woolley was from a constituent to a Commissioner. From a rancher who believed he could lose his land, his livestock, and his livelihood, not to mention his own health and that of his family’s, to his County Commissioner charged with protecting public health.

Little did Woolley know at the time, this call and what followed would represent a turning point in a startling story that has gained momentum and, at times, brought Woolley to tears.

One year earlier, another Johnson County rancher had come to the county to express concern about the effects of “sludge” or “biosolids” fertilizer being spread by a farmer on a neighboring property.

During wastewater treatment, liquids are separated from solids. Those solids are then treated physically and chemically to produce a semisolid, nutrient-rich product known as biosolids, as explained by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Biosolids, sometimes referred to as sludge, are divided into Class A and Class B with the designations based on treatment methods.

Both ranchers believe the sludge fertilizer spread by the farmer has contaminated their land and sickened both animals and members of their families.

Woolley had already paid Coleman a personal visit. Woolley witnessed the piles of fertilizer on the farmer’s land, smelled the unbearable stench, and looked at Coleman’s animals and his ranching operation. Woolley asked Coleman to let him know if/when another animal died so the tissue could be taken for immediate testing.

Coleman called Woolley with news of the stillborn calf on a Saturday. That next Monday morning, Woolley and Detective Dana Ames picked up the calf from Coleman’s ranch. Ames, who works environmental crimes for the Office of Johnson County Constable Pct. 4, was careful to take photos to verify chain of custody, as the carcass was now evidence, before loading the stillborn into Woolley’s pickup.

Ames and Woolley delivered the black stillborn calf encased in ice to the Texas A&M Veterinary Medical Diagnostic Laboratory (TVMDL) in College Station. There the calf underwent a necropsy, or the examination of the dead body or carcass of an animal, similar to an autopsy conducted on humans.

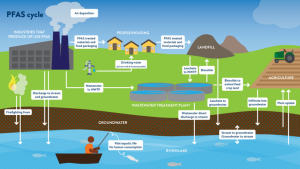

TVMDL sent the tissue samples to a lab in Pennsylvania and asked the lab to test for PFAS, or per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances. PFAS is an umbrella term for thousands of manufactured chemicals that have been used in industry and consumer products since the 1940s (further explained later in this article).

The lab results left Woolley and Ames speechless, and here’s why: In March 2023, the EPA proposed maximum contaminant levels (MCLs) for six PFAS chemicals in drinking water including 4 parts per trillion (ppt) for the chemical PFOA and 4 ppt for the chemical PFOS. Incidentally, the MCLs were officially adopted by the EPA in April 2024. Visually speaking, an MCL of 4 ppt equates to 4 drops of paint in a body of water about the size of 20 Olympic swimming pools combined, Ames explained. The liver of the stillborn calf measured 610,000 ppt of PFOS, a major chemical in the PFAS group of chemicals.

Water is considered contaminated at over 4 ppt of PFOS, Ames reiterated, and the calf’s liver measured 610,000 ppt of PFOS, she repeated.

By the time the county received the test results, Ames had already spent a year researching the case, combing through reports and documents from scientists, labs, and federal agencies. She had also overseen the testing of soil, water, and animal and fish tissue samples in and around the affected ranchland.

In her research, Ames learned that while the EPA and the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) do regulate biosolids, those regulations were established more than 30 years ago and cover only a handful of substances, not PFAS.

She discovered that several PFAS chemicals, including PFOA and PFOS, have now been linked to multiple cancers and other health issues, according to the National Institute of Health and the National Cancer Institute.

Ames learned that PFAS can be ingested, inhaled, or absorbed through the skin. Multiple sources explained that PFAS chemicals can build up in people, animals, and the environment and take a very long time to break down; for these reasons, they are often described as “forever chemicals.” Armed with this knowledge, the 610,000 ppt of PFOS in the liver of the stillborn calf left Ames and Woolley stunned and shaken.

“We knew we had a major problem,” Ames recalled. “From then on, this case took ahold of me, and I cannot let it go. I can’t ‘unknow’ what I know,” she shared with emotion.

Case Chronology

A Foul and Offensive Stench

About four years before an official complaint was filed and five years before the calf tissue was tested, Woolley and Ames had heard from residents about an unbearable, noxious smell and made a general inquiry into the cause.

“I was shocked to learn that processed human waste was part of a substance being applied as fertilizer,” Ames recalled, “and that this method was approved by the EPA.”

It seemed that residents would have no choice but to live with the overwhelmingly foul odor until the first complainant suspected the smell was a mere prelude to numerous offenses with dire consequences.

County Launches Official Investigation

Ames was contacted by the first rancher in late December 2022, as described in Ames’ official report:

Dec. 29, 2022

- Complainant advises neighbor is spreading sewage sludge/biosolids/fertilizer that has been smoking for days.

- Complainant advises the valley surrounding his property has filled up with smoke.

- Complainant advises the smoke is creating breathing problems for him, his wife, and neighbors.

- Complainant advises previous spreading of sewage sludge/biosolids has caused all the fish to die in his ponds and his neighbor’s ponds.

- Complainant believes the sewage sludge/biosolids has been causing him, his wife, and animals to become physically ill.

Dec. 30, 2022

On this date at approximately 1440 hours, Ames arrived at the subject’s property located in Grandview, Johnson County. Upon arrival, Ames observed approximately 12 -15 very large black piles of what appeared to be sewage sludge/biosolids smoldering and putting off large plumes of smoke. The odor coming from the piles was a musty chemical smell. Ames observed a green tractor scooping up the piles of biosolids and dumping the material into a large yellow spreading vehicle. Ames made contact with a male subject spreading the material; the subject later advised the product he was spreading was a product called Synagro Granulite Fertilizer. This “fertilizer” is made from Class A Biosolids/Municipal Wastewater Treatment Sludge from the city of Fort Worth.

Commissioners Court Response

On April 10, 2023, the Johnson County Commissioners Court approved a request from Ames for $30,000 for soil and water testing. After multiple animals passed away, Johnson County Constable Troy Fuller went back to the court to request funding for necropsy and tissue testing; an additional $5,000 was approved.

“We allocated funding to allow Investigator Ames to retain the services of a laboratory to conduct testing on soil and water samples,” Johnson County Judge Chris Boedeker detailed. “Later, the court acted to allocate additional funding to allow for further testing, including groundwater and animal and fish tissue samples. When the results of the testing came back, the court took official action requesting that Investigator Ames prepare a report and presentation to make the public aware of the results of her investigation.”

In order to ensure integrity without question, Johnson County used an independent lab, Eurofins Lancaster Laboratories Environment Testing, LLC, out of Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

On Feb. 16, 2024, after her year-long investigation including collaboration with scientists and other experts, Ames presented her findings at a special Commissioners Court meeting.

“In the areas we are talking about today, Texas counties, no county of Texas has authority over the land application of biosolids,” Woolley stated in introductory remarks. “That is a state-regulated authority that goes through TCEQ. Counties have asked for that authority. We have asked the legislature for that, and it has fallen on deaf ears…We are charged with public health and public safety, and that is what triggered this investigation.”

Ames shared handouts and used slides to communicate the sobering situation.

While the EPA and TCEQ do regulate biosolids, the regulations were established over three decades ago and include very few substances, she emphasized.

“Since that time much has changed as we have become a more industrialized nation and new chemicals have been introduced into a myriad of commonly used products,” Ames articulated. These chemicals are used in everything from fire retardants to adhesives to coating for armored tanks.

Several PFAS, including PFOA and PFOS, have now been linked to kidney cancer, testicular cancer, infertility, and low testosterone levels and are suspected in thyroid cancer and other cancers, according to the National Institute of Health and the National Cancer Institute.

Ames presented results detailing the high PFAS levels in Johnson County from multiple test sites and from animal and fish tissue samples.

On Feb. 15, 2024, five farmers and ranchers from Johnson County sued Synagro Technologies alleging high levels of PFAS in fertilizers produced by Synagro. The suit claims Synagro did not warn of the harmful effects of PFAS. In a public statement, Synagro said it will be contesting the lawsuit; the company denied the allegations, calling them unproven and novel. Due to the pending litigation, the ranchers are not available to comment on the lawsuit.

On March 25, 2024, the Johnson County Commissioners Court passed a local resolution calling for the prohibition of the application of biosolids, available at https://bit.ly/biosolidrez.

On May 13, 2024, the Johnson County Commissioners Court voted to join a lawsuit and file a Notice of Intent to Sue the United States Environmental Protection Agency.

“This litigation will not cost our county any money nor will there be any monetary award sought,” Woolley emphasized. “The intent of the suit is for the EPA to regulate PFAS in biosolids similar to the recently adopted acceptable levels of PFAS in drinking water.”

The county is represented by the legal team at Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility (PEER), a 501(c)(3) organization located in Silver Spring, Maryland.

“Ideally, the ultimate goal would be for all land application of biosolids to stop or at least guarantee that all biosolids are safe,” Woolley elaborated. “The other goal is for all the contamination to be cleaned up to the point that the land would be considered safe to grow crops and livestock, and to live with an assurance that we as humans are safe.”

Johnson County’s criminal investigation is still open.

“The county’s goal in this is to protect the ranchers, farmers, and farmland that form the backbone of our community,” Boedeker declared. “To accomplish that goal, we need to prevent further contamination of our soil, water, and agricultural products; in other words, we have to stop the bleeding,” he continued. “If biosolids can be applied in a manner that does not damage the agricultural community, then we have no objection to their use. But if biosolids cannot be safely applied, they should be prohibited.”

City, State, and Federal Response

In April of 2020, Synagro assumed operation of the city of Fort Worth’s biosolids management facility and program.

“The beneficial reuse of biosolids through land application is encouraged by state and federal environmental regulators, as it provides an agricultural benefit while preserving landfill space,” said Mary Gugliuzza, media relations and communications coordinator for Fort Worth Water. “Land application of Fort Worth biosolids must comply with all applicable state and federal biosolids rules, which have been designed to protect both the public and the environment. Across the country, according to the U.S. EPA, about 60 percent of biosolids produced in the United States are applied to land as an agricultural amendment,” Gugliuzza continued.

“Fort Worth will not further comment on this matter because it’s about active litigation,” she added.

While the TCEQ is aware of the situation, the agency did not perform testing as Johnson County enlisted the services of PEER to assist with testing, according to Laura L. Lopez, TCEQ media and community relations manager. The TCEQ “is not currently involved in this matter,” Lopez said at press time.

“The EPA does not currently regulate any PFAS in biosolids under the Clean Water Act,” confirmed EPA press secretary Remmington Belford. “The agency is taking important steps to research, restrict, and remediate PFAS chemicals in the environment, as described in the EPA PFAS Strategic Roadmap, available at https://bit.ly/EPAPFASroadmap.”

The EPA is currently assessing risks associated with the use of biosolids and the disposal of sewage sludge containing PFOA and PFOS and expects to publish the risk assessment by the end of 2024, Belford continued. The risk assessment will focus on risks to human health through exposures to contaminated soil, drinking water, crops, meat, dairy, and eggs resulting from biosolids land application to farms.

“This is a necessary first step to determine whether regulation of PFOA and/or PFOS in sewage sludge is warranted under the Clean Water Act,” Belford stated.

In addition, the EPA is embarking on a study to better understand the occurrence of PFAS chemicals in wastewater and sewage sludge nationwide, he continued.

“While these agency actions are underway, EPA recommends that states monitor sewage sludge for PFAS contamination, identify likely industrial discharges of PFAS chemicals, and implement industrial pretreatment requirements where appropriate,” Belford added.

Moving Forward

Joining the lawsuit against the EPA is not a stopping point. Rather, Ames said she will continue researching, and Woolley will continue collaborating with lawmakers until change is accomplished. The fuel behind their fire includes not only the people of Johnson County, but those in neighboring counties and beyond.

“The PFAS in the biosolids fertilizer in Johnson County presents a major problem for all communities, as these contaminants do not stop at any county border and seriously threaten our food supply, drinking water, and health,” Ames underscored.

Woolley can’t help but take the matter personally, not only as a county official charged with public safety, but also as a lifelong rancher.

“These people go to bed every night knowing that they are going to wake up the next day and continue to be exposed to dangerous chemicals,” Woolley shared. “This family owns approximately 75 mother cows that all have calves at this time, so that is 150 beef cattle that could potentially be deemed unsafe to enter the food chain, yet they are forced to continue feeding them and caring for them while we all wait to see what is going to happen here.”

“As a rancher and a farmer, that hits me hard,” Woolley added. “These families live in uncertainty not knowing their future in terms of their livelihood as well as their own personal health.”

In the meantime, Woolley said he will continue moving forward, actively working with state and federal legislators.

Several years ago, Johnson County officials presented a resolution to the County Judges and Commissioners Association of Texas (CJCAT) requesting “that no permits be issued for the disposal of sludge and biosolids waste without the approval of the Commissioners Court and that the Texas Legislature clearly authorize local control of all sludge and biosolids waste permits.” Woolley will continue to promote passage of that resolution by the CJCAT.

Biosolids Development and Disposal History

Prior to 1992, biosolids were dumped into the ocean. The Ocean Dumping Ban Act of 1988 amended the Marine Protection, Research, and Sanctuaries Act, commonly called the “Ocean Dumping Act,” and made it “unlawful for any person to dump or transport for the purpose of dumping sewage sludge or industrial waste into ocean waters after Dec. 31, 1991,” as explained by the EPA at https://bit.ly/dumpingban.

The Federal Water Pollution Control Act, known as the Clean Water Act, was then amended to address biosolids regulation. The Standards for the Use or Disposal of Sewage Sludge (Title 40 of the Code of Federal Regulations [CFR], Part 503), was published in the Federal Register on Feb. 19, 1993, and became effective on March 22, 1993. The regulation is commonly referred to as Part 503.

In an EPA-approved document, “A Plain English Guide to the EPA Part 503 Biosolids Rule,” Michael B. Cook, director of the EPA’s Office of Wastewater Management, and his team explain how biosolids are regulated. The guide, available at https://bit.ly/epabioguide, was published in September 1994, over 30 years ago.

Part 503 regulates the final use or disposal of biosolids when applied to land to condition the soil or fertilize crops or other vegetation grown in the soil, when placed on a surface disposal site for final disposal, or when fired in a biosolids incinerator.

The state agency tasked with monitoring and enforcing these federal regulations is the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ).

When Part 503 went into effect over 30 years ago, many chemicals used today did not exist or were not known about, said Detective Dana Ames, environmental crimes investigator for the Office of Johnson County Constable Pct. 4. In fact, there were only certain substances including heavy metals that the EPA and TCEQ focused on, Ames explained.

“Since biosolids were approved for land application, much has changed as we have become a more industrialized nation and new chemicals have been introduced into a myriad of commonly used products,” Ames summarized. For the last three decades, thousands of toxic chemicals used in everything from fire retardants to adhesives to coating for armored tanks have been developed and refined. These chemicals are now referred to as PFAS, an umbrella term that stands for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances.

In March 2023, the EPA proposed maximum contaminant levels for six PFAS chemicals in drinking water including 4 parts per trillion (ppt) for the chemical PFOA and 4 ppt for the chemical PFOS. In April of 2024, the EPA finalized these levels and released an official statement saying the agency is “taking another step in its efforts to protect people from the health risks posed by exposure to ‘forever chemicals’ in communities across the country.” The statement goes on to discuss a ‘final rule’ that “builds on the recently finalized standards to protect people and communities from PFAS contamination in drinking water,” as stated at https://bit.ly/epaPFASupdate.

“The EPA does not currently regulate any PFAS in biosolids under the Clean Water Act,” confirmed EPA press secretary Remmington Belford. “The agency is taking important steps to research, restrict, and remediate PFAS chemicals in the environment, as described in the EPA PFAS Strategic Roadmap,” available at https://bit.ly/EPAPFASroadmap.