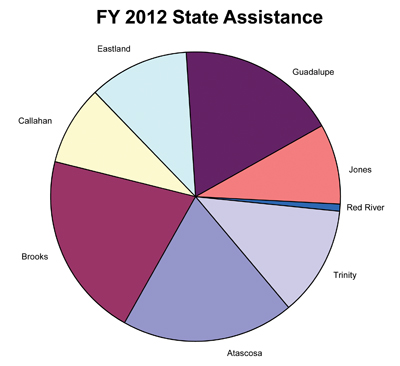

Eight Texas counties received $223,768 in state matching funds in 2012 to help offset the cost of indigent health care compared to last year’s disbursement of $2.6 million in state support, according to the latest reports.

The Indigent Health Care and Treatment Act of 1985 requires counties that are not completely covered by a hospital district or public hospital to provide basic health services to indigent residents through a county-run County Indigent Health Care Program (CIHCP); Texas is home to 143 CIHCPs. Each fiscal year a county is liable for $30,000 or 30 days of hospitalization or nursing-home care per eligible resident, whichever comes first.

Once a county spends 8 percent of its general revenue tax levy (GRTL) on indigent care, the county can then request state matching funds, with the state reimbursing the county at least 90 percent of all costs above the 8 percent spending level.

If the department fails to provide state assistance funds, the county is not liable for payments for health care services provided to its eligible residents after the county reaches the 8 percent expenditure level, specified Jan Maberry, manager of the Department of State Health Services (DSHS) CIHCP.

The 81st Legislature appropriated an original amount minus a post-session reduction that netted a total of $9,380,404. The 82nd Legislature’s appropriated amount totaled $4,403,759, a decrease of some 53 percent.

“This decrease in funding will have an impact on the counties that have historically received state funds,” Maberry predicted. The state assistance fund was reduced from $2.6 million in FY 2011 to $223,768 in FY 2012, meaning less support was available; however, all of the available funds were allocated to the eight counties that requested money.

“Several counties reported closing their programs by not paying any medical claims after expending local funds and receiving state funds,” Maberry related. “Others reported modifying their programs to serve their existing patients with limited services such as prescription drugs and preventive care, only, and not accepting new applications.”

At press time Red River County was in the process of issuing a letter to all of its indigent health care clients and vendors stating the county would be shutting down its program the last day of March.

“This does indeed leave a long period of time for these people to be without assistance,” declared Red River County Judge Morris Harville. “It is a tragedy for this to occur in our county, when the adjacent counties have sufficient funds to provide for their people the rest of the year.

“If people happen to live in a wealthy county, they will receive better care than if they happen to live in a poor, rural county,” Harville maintained. “Every year we can barely make our budget, yet we must set aside 8 percent of that amount for the care of our indigent population, which is a large percentage of our population.”

This time last year Harville alluded to another potential aid which continues to unfold, the Texas Health Care Transformation and Quality Improvement Program 1115 Waiver, known simply as the 1115 Waiver. In December 2011, Texas received approval from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services for a waiver that allows the state to expand Medicaid managed care while preserving hospital funding, provides incentive payments for health care improvements, and directs more funding to hospitals that serve large numbers of uninsured patients. This waiver replaces the current Upper Payment Limit (UPL) program and will be in effect until September 2016.

This time last year Harville alluded to another potential aid which continues to unfold, the Texas Health Care Transformation and Quality Improvement Program 1115 Waiver, known simply as the 1115 Waiver. In December 2011, Texas received approval from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services for a waiver that allows the state to expand Medicaid managed care while preserving hospital funding, provides incentive payments for health care improvements, and directs more funding to hospitals that serve large numbers of uninsured patients. This waiver replaces the current Upper Payment Limit (UPL) program and will be in effect until September 2016.

The DSHS touts the 1115 Waiver as an opportunity for counties to examine their current health care delivery systems and explore partnerships within their communities to help their indigent populations. (http://www.hhsc.state.tx.us/1115-waiver.shtml.)

“While the Section 1115 Medicaid Waiver funding may relieve some of the county indigent health care burden, we will need to evaluate this impact as the projects are implemented during the next four years,” proposed Jim Allison, general counsel to the County Judges and Commissioners Association of Texas.

With 10 percent of the waiver funding dedicated to mental health services, counties should see some increase in these services, Allison added. Additional projects for diabetes control and reduction in emergency room visits and hospital re-admissions should also produce some reduction in county health care costs.

Basic, Optional Services

In order to qualify for state matching funds, counties are required to provide basic health care services to eligible residents and may elect to provide a number of DSHS-established optional health care services, Maberry explained. Specifically, counties must provide the following:

Immunizations

Medical screening services

Annual physical examinations

Inpatient hospital services

Outpatient hospital services, including hospital-based ambulatory surgical center services

Rural health clinics

Laboratory and x-ray services

Family planning services

Physician services

Payment for not more than three prescription drugs per month

Skilled nursing facility services

Optional health care services include the following DSHS-established services:

Ambulatory surgical centers (freestanding) services

Diabetic and colostomy medical supplies and equipment

Durable medical equipment

Home and community health care services

Psychotherapy services provided by a licensed clinical social worker (LCSW), a licensed marriage family therapist (LMFT), a licensed professional counselor (LPC), or a psychologist

Physician assistant services

Advanced practice nurse – a nurse practitioner, a clinical nurse specialist, a certified nurse midwife (CNM), or a certified registered nurse anesthetist (CRNA)

Dental care

Vision care, including eyeglasses

Federally qualified health center (FQHC) services

Emergency medical services

Physical and occupational therapy services

Other medically necessary services or supplies that the local governmental municipality/entity determines to be cost-effective

Effective March 2008, the optional health care services category was expanded to include “any other appropriate health care service that the local governmental municipality or entity deems appropriate and cost-effective,” Maberry recounted.

Before this addition if a county wanted to pay for a particular service or equipment and it was not specifically in the rules, the county would not be eligible for state matching funds for that service or equipment, even if the county surpassed its 8 percent. With this change, these other expenditures can count toward the counties’ 8 percent expenditure and be eligible for state matching funds, Maberry said.

Training Opportunities

Commissioners courts interested in learning more about the varied aspects of their county’s indigent health care program are eligible to attend training sessions offered by DSHS.

“I encourage judges and commissioners to learn as much as they can about the program,” Maberry emphasized. “Don’t go into it blindly. After all, you’re potentially going to spend quite a bit of money on indigent health care.”

DSHS conducted four training sessions in Austin during FY 2012 and also conducted training in Arlington, Falfurrias, Houston, Lubbock and Odessa. Thus far in FY 2013, training has taken place in Tyler (September) and Austin (October and January). The upcoming training dates and locations are yet to be determined, Maberry indicated. Counties requesting training for their program coordinators may e-mail the program at ihcnet@dshs.state.tx or refer to the program website: http://www.dshs.state.tx.us/CIHCP/Training.shtm.

The target audience includes those who administer the CIHCP for their county, hospital district or public hospital. The training classes are beneficial for new staff, supervisors, and those simply needing a refresher course.

“I think it’s an excellent idea for commissioners court members to attend,” suggested Karen Gray, program specialist and primary care group trainer with DSHS. “Even though you may not have a direct, hands-on responsibility or position with the indigent program, if it’s something that you manage or falls under your jurisdiction, it would be an excellent idea for you to attend.”

The classes cover Chapter 61 and include eligibility and bill payment policies, Gray described. Classroom instruction is followed by hands-on exercises designed to “put the knowledge and new skills to the test.”

For example, participants are presented with unique situations, such as a self-employed applicant who does not have thorough bookkeeping in place, or a single mom who receives child support. Indigent health care applicants usually present extenuating circumstances; they are not your “typical two-parent, two-child, dad works, and mom stays at home with the kids” household, Gray explained.

“We try to give participants the skills to handle the many unique situations,” she continued. And while the training certainly won’t address all possible scenarios, it will give trainees a head start.

Throughout the past few years, a couple of commissioners court members have pursued DSHS training, Gray reported.

“I think they do understand the program a lot better after they learn the complexities of eligibility and bill payment,” Maberry added.

Gray concurred, describing the training as an “eye-opening process” that would help commissioners courts appreciate the needs of their indigent health care departments.

To learn more about the County Indigent Health Care Program including handbook revisions, spending data and training dates, go to

www.dshs.state.tx.us/cihcp.