Editor’s Note: The following is Part 1 in a series from “Overincarceration of People with Mental Illness, ” a report released in June 2015. The full report is available at rightoncrime.com/2015/06/overincarceration-of-people-with-mental-illness/. We will continue the series in our April issue.

By Kate Murphy and Christi Barr

Center for Effective Justice Texas Public Policy Foundation

Introduction

Paton Blough, who has bipolar disorder, describes mania as feelings of nirvana and ultimate power alternating with feelings of extreme fear and paranoia.1 Ten years ago, Bough experienced a manic episode that made him believe a police officer was trying to pull him over to murder him.2 This belief led to a high speed chase and Bough’s first arrest.3 In jail, Bough believed he was waging nuclear war with China by sending signals to President Bush from his jail cell.4 He was eventually moved to a mental health hospital.5 During the three years following his initial release, he experienced alternating episodes of mania and depression.6 He was arrested six times and received several misdemeanor convictions and two felony convictions.7 Although ashamed of his criminal record, Bough has since used his experiences to help train more than 250 police officers in crisis intervention.8

Bough is not alone in his interactions with the criminal justice system. Texas county jails house around 60,000 to 70,000 inmates per day. On March 1, 2015, the Texas Commission on Jail Standards reported that 63,159 people were in county jails.9 Of the 63,159 people in jail on March 1, 2015, 60 percent (37,893) were awaiting trial.10 A 2012 study of five U.S. jails by Fred Osher et al. found that 17 percent of adults entering jails met the criteria for serious mental illness (SMI).11 If this holds true in Texas, county jails hold about 6,400 pretrial detainees with serious mental health issues every day. With counties in Texas spending an average of $59 per inmate per day,12 this suggests an annual cost of about $138.7 million for pretrial detainees with mental health issues.

But cost is not the only problem facing Texas communities. The criminal justice system is not designed to treat people with mental illness. People with mental illness also have higher recidivism rates.13 Additionally, some pretrial diversion programs appear to reduce recidivism and lead to positive outcomes for participants, including less time incarcerated, avoidance of criminal convictions, and improved substance use and mental health outcomes.14 Pretrial diversion and treatment appear to be better than incarceration at addressing the problems often associated with people with mental illness who have committed crimes.

Of course, this shouldn’t be a surprise. Prisons and jails are not mental health treatment facilities – they are detention facilities intended to deter crime, punish criminal activity, or encourage personal reform. Further, law enforcement officers traditionally are not trained to counsel people with mental illness – they are trained to enhance public safety sometimes through arrest and incarceration.

Following arrest, people are taken to jail intake where corrections officers gather information to inform decisions regarding the unit of assignment, the level of security supervision, housing and job assignments and time-earning status, and whether an assessment would be prudent to identify any treatment or special needs. Generally within 48 hours, the detainee will appear before a judge or magistrate who will determine whether that person can be released on bail or bond. If not, the individual will be held in jail until his or her case is adjudicated. The longer people with mental illness are in jail, the lesser their likelihood of success may be upon release particularly if they do not receive adequate treatment. Because of this concern, early mental health screening and assessment are an important part of any effective diversion strategy.

Many people with serious mental illness who have also committed serious crimes should be incarcerated. But for others, diversion may be more appropriate. The first challenge, then, is increasing the ability to identify those who might be safely diverted from the criminal justice system to reduce future repeat interactions with the system, which will be a significant focus of this paper. The criminal justice system presents many opportunities to link offenders with serious mental illness to services that might prevent recidivism. This study will focus on diversion programs for people with mental illness.

However, increasing the effectiveness of various pretrial diversion programs will not fix all of Texas’ problems. In Texas the state controls and funds most public mental health services, but local governments are better situated to address problems in their community surrounding people with mental illness. The lack of coordination between the local governments that provide criminal justice and law enforcement services and the state government that provides mental health services is a significant problem. As a result, local government does not always have the ability or resources to take actions to resolve the problems arising from the apparent lack of coordination. This study will also examine this problem.

The Scope of the Challenge

Most people understand that these days, jails across our country serve as de facto mental institutions. In Texas, 30 percent of jail inmates have received mental health services from the state.15 The Harris County Jail, often cited as the largest mental health facility in the state, doses about 2,500 people with psychotropic medication every day.16 In Bexar County, the former Commander of the Mental Health Division of the Sheriff’s Office reported that mental health consumers spend twice as long in jails as non-consumers for the same offense and cost taxpayers two to three times more money.17

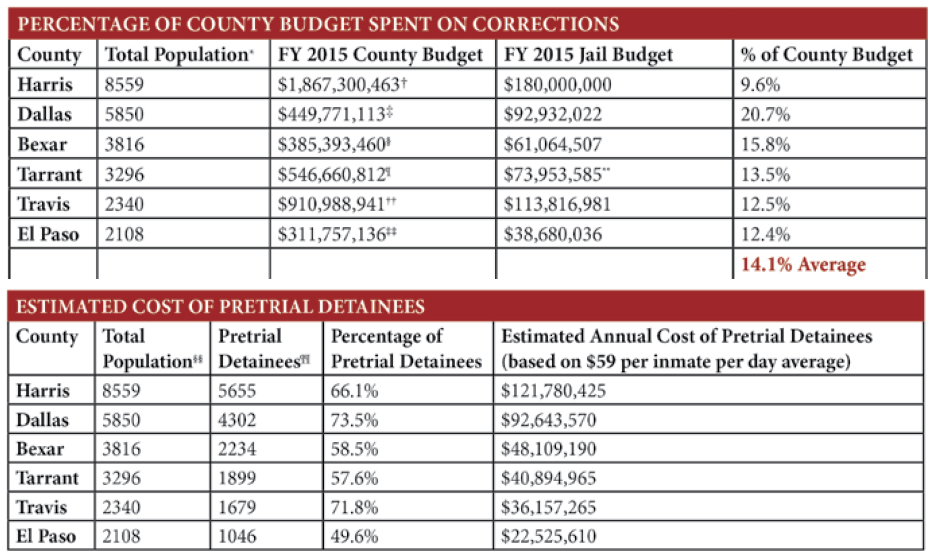

Beyond spending more time in jail and costing taxpayers more money, people with mental illness also have more repeat incarcerations. For example, in 2006-07 the Urban Institute studied patterns of mental illness in the criminal justice system and found that incarcerated Texans with psychiatric disorders were 2.4 times more likely to have four or more repeat incarcerations.18 For those with bipolar this number rose to 3.3.19 Placing people with mental illness in local jails costs money, just as dealing with crime in general does, at both the state and local levels. The chart that follows shows the percentage of several county budgets that is spent on these large populations.

An average of 14.1 percent of the county budget for several large counties in Texas is spent on corrections. The following chart focuses on the cost of pretrial detainees in the largest county jail populations in Texas. Many jails that feel overburdened by people with mental illness in their facilities are calling for greater state mental health hospital capacity, but the state’s mental health hospitals are more expensive and are also overcrowded.

The criminal justice system is putting enormous pressure on the state mental health hospitals. The Texas Sunset Advisory Commission, which examined the state hospital system, found that “resolving the current [capacity] crisis in the state mental health hospital system requires action, starting now.”20 Inpatient psychiatric beds do not meet the demand of the communities using them. This crisis has largely been driven by the growing forensic population. People who are committed to state hospitals because they were deemed incompetent to stand trial are part of the forensic population.21 In 2014, for the first time in Texas history, forensic commitments outnumbered civil commitments. Forensic commitments include those held incompetent to stand trial and those found not guilty by reason of insanity; all other consumers are civil commitments. And in 2013, inpatient psychiatric beds were unavailable to communities for over one-third of the year, particularly hurting rural communities with less local options.22 Forensic patients also stay in state hospitals longer. Civil and voluntary patients stay for on average 49 and 30 days respectively, while those found not guilty by reason of insanity and or incompetent to stand trial stay for an average of 370 and 135 days.23 Increased forensic pressure strains the state hospitals by reducing the amount of beds available to all new patients seeking treatment and limiting access to care for civil and voluntarily commitments.

The large number of arrests and the sizable county jail populations in the U.S. have made pretrial diversion programs very popular across the board, not just in addressing people with mental illness.

Over the 2014-15 biennium the 83rd Legislature appropriated $2.6 billion to the Department of State Health Services (DSHS) for mental health services: $665 million for adult community mental health service,24 $201 million for children’s community mental health services,25 $221.2 million for community mental health crisis services,26 $226.6 million for NorthSTAR,27 $315.6 million for substance abuse services,28 $837 million for state mental health hospitals,29 and $153.1 million for community mental health hospitals.30 But state funding of behavioral health services actually amounts to $3.2 billion across all state agencies.31 And this $3.2 billion does not include federal funding, Medicaid, or local funding.

Since its establishment in 2003, DSHS has failed to provide integrated, outcomes-focused community behavioral health services.32 Not only are community-based behavioral health services generally more pragmatic and humane, but they are also typically more cost effective than services provided in state institutions and are better at improving outcomes.33 Effective community behavioral health services go a long way to reduce pressure on jails and local communities.34 Texas has been mismanaging mental health resources for at least the last 12 years, which has contributed to a pattern of overcriminalization or overincarceration of people with mental illness. But the truth is that Texas’ public health and corrections systems likely have enough money to address this problem if the system was run more efficiently, which would be most easily accomplished by delegating the responsibility to local governments.

Pretrial Diversion

Pretrial diversion programs provide an alternative to traditional criminal justice processing. These programs have arisen as a response to state failure to provide effective mental health services, as have other diversion strategies on which law enforcement currently relies. As implemented most diversion programs target offenders who would be better served through community-based services rather than going through criminal processing.35 The programs all involve several core elements, including a set of eligibility criteria, structured delivery of services and supervision, and dismissal of charges after successful completion of the program.36 Community-based treatment programs can be effective at stabilizing individuals and making recommendations to address long-term behavioral health needs that will prevent people from cycling through various, expensive state institutions.37

A recent report by the Texas Public Policy Foundation documented that “in 2012, there were 12.2 million arrests in the U.S., according to the FBI. About 220,000 people are admitted to county jails every week whereas state prisons admit 10,000 per week. Nationally, 62 percent of jail inmates are pretrial detainees, with the remainder being those convicted and serving a sentence for misdemeanors, and others convicted of felonies who are waiting to be picked up by the state prison system.”38 The large number of arrests and the sizable county jail populations in the U.S. have made pretrial diversion programs very popular across the board, not just in addressing people with mental illness.

The Foundation goes on to describe the goals of pretrial diversions policies: These goals typically fall into the following categories:

- making sure the defendant shows up for hearings and trial so that justice can be dispensed,

- ensuring that the public is protected from defendants committing crimes during the period prior to trial,

- observing constitutional rights to reasonable bail and due process that apply to those arrested but not yet convicted, and

- controlling jail costs, which are the largest expense in many county budgets.

These considerations require balancing the cost of keeping the accused in jail against the risks that, if released, he will not appear for his trial and may even commit a new offense. Either entails the cost of finding and securing him and, in the case of a new offense, a possible cost to a victim.39

An additional challenge when addressing offenders with mental illness is finding the best treatment setting that will help reduce recidivism. Another factor to be considered is that treatment alone is not always sufficient. Symptoms of mental illness only directly cause about 17 percent of crimes.40 And many offenders with mental illness commit crimes that are not motivated by symptoms of mental illness.41 The sometimes tenuous link between mental illness and crime demonstrates the importance of cognitive adaptive training that imparts new skills and knowledge to offenders who are diverted from jail and remain in society. Therefore, good pretrial diversion programs for people with mental illness should often include both treatment and other services that address criminogenic behavior.

Editor’s Note: Part 2 of this series will run in our April issue and begin with the sub-topic: Pretrial Diversion Programs and Practices in Texas.

* Texas Commission on Jail Standards, http://www.tcjs.state.tx.us/docs/AbbreRptCurrent.pdf (Mar. 1, 2015).

† Harris County, FY 2014-15 General Fund Budget – Approved February 11, 2014 (Feb. 11, 2014).

‡ Dallas County, Dallas County Approved Budget FY 2015 (Oct. 1, 2014-Sept. 30, 2015).

Bexar County, Proposed Annual Budget Fiscal Year 2014-15 (Oct. 1, 2014-Sept. 20, 2015).

¶ Tarrant County, Tarrant County, Texas FY2015 Adopted Budget (2015)

** Tarrant County, General Fund Summary (2015)

†† Travis County Planning and Budget Office, Travis County Fiscal Year 2015 Budget Summary (Oct. 2014)

‡‡ El Paso County, County of El Paso, Texas, Adopted Budget, Book 1 of 4, (Oct. 7, 2014)

§ Texas Commission on Jail Standards, http://www.tcjs.state.tx.us/docs/AbbreRptCurrent.pdf (Mar. 1, 2015).

¶ ¶ Texas Commission on Jail Standards, http://www.tcjs.state.tx.us/docs/AbbreRptCurrent.pdf (Mar. 1, 2015).