Inexpensive Tool Yields Impressive Results

By Julie Anderson

Editor

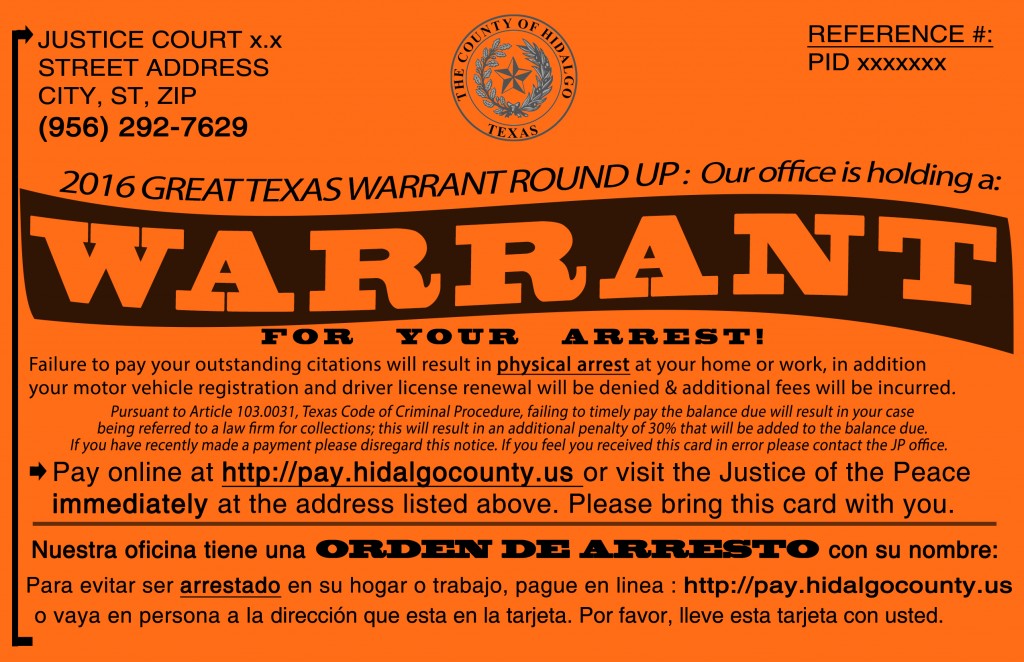

The approach appears tough – bold letters, all caps indicating a “WARRANT FOR YOUR ARREST.” However, the “message behind the message” is actually somewhat merciful: “We don’t want to put you in jail, so please pay now.”

Hidalgo County launched its Warrant Postcard Program in 2015 giving defendants the opportunity to clear their active warrants and avoid the chance of arrest, an initiative that has clearly paid off considering first-year results: $1,834,292.86 collected from 94,263 cases.

“We were looking for ways to be more efficient,” explained Julia Benitez Sullivan, Hidalgo County public affairs director. Because of the first year’s success, the county opted to repeat the effort in 2016.

This program allows individuals with warrants to settle their accounts, Sullivan summarized, and also frees constables’ time from serving routine warrants for minor violations. Constables are then able to concentrate on more serious offenses, such as those with a high volume of warrants and individuals with criminal warrants.

Prior to the Warrant Postcard Program, “my officers had to go door to door, which was not the most efficient use of resources,” shared Hidalgo County Constable Martin Cantu during a press conference publicizing the 2015 postcard initiative.

All four county constables and eight justices of the peace in Hidalgo County are participating in the program. Once the fine is paid, the warrant is cleared, and the resident does not have to worry about being arrested.

“We are targeting 28,218 warrants that total $8.8 million in fines,” stated Ricardo Rodriguez Jr., criminal district attorney, when announcing one of the early 2016 mailouts; the county sends out several batches of post cards throughout the year.

During 2015, Hidalgo County mailed about 11,000 postcards with warrants issued from 2012 through February 2015. The program cost the county approximately $7,000 for the printing and mailing service last year; the service used by the county verifies the address to reduce the chances of returned mail.

The county has mailed two batches so far in 2016.

As noted on the postcard, if the fines remain unpaid, the arrests can take place at any location, including the defendant’s home, school or workplace.

The program more than pays for itself, Sullivan maintained, and has been an effective tool to collect delinquent fines and fees.

Mandated Collection Programs

In 2005, the 79th Texas Legislature addressed county collections via the passage of Senate Bill 1863 requiring counties of 50,000 or more to develop and implement a program to collect court costs, fees and fines imposed in criminal cases to include district, county and justice courts, unless granted a waiver, http://www.txcourts.gov/cip/about-the-cip.aspx. This statute requires cities with a population of 100,000 or more and counties with a population of 50,000 or more to implement a Collection Improvement Program (CIP) based on a model developed by the Office of Court Administration (OCA). Population is based on the most recent federal decennial census. Prior to the 2010 federal census, a total of 78 counties and cities were required to implement a program, Based on the 2010 federal census, an additional eight counties and five cities were required to implement a program, resulting in a total of 91 programs (62 counties and 29 cities).

The required provisions are:

- conform with the OCA model, which is designed to improve in-house collections through application of best practices; and

- improve collection of balances more than 60 days past due, which may be implemented by entering into a contract with a private attorney or public or private vendor. According to state law, a 30 percent fee can be assessed on a fine or fee, which is the firm’s payment for collection.

Key Elements of the Collection Improvement Program

- Staff or staff time dedicated to collection activities.

- Expectation that all court costs, fees and fines are generally due at the time of assessment (sentencing or judgment imposed date).

- Defendants unable to pay in full on the day of assessment are required to complete an application for extension of time to pay.

- Application information is verified and evaluated to establish an appropriate payment plan for the defendant.

- Payment terms are usually strict.

- Alternative enforcement options (e.g., community service) are available for those who do not qualify for a payment plan.

- Defendants are closely monitored for compliance, and action is taken promptly for non-compliance:

- telephone contact and letter notification are required when a payment is missed;

- possible issuance of a warrant for continued non-compliance; and

- possible application of statutorily permitted collection remedies, such as programs for non-renewal of driver’s license or vehicle registration.

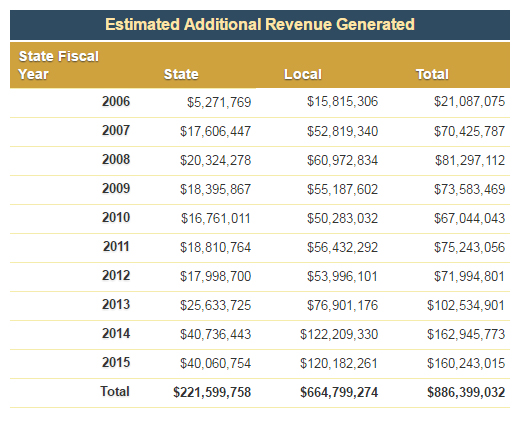

The estimated additional revenue for the required/mandatory cities and counties is based on revenue reported to the Comptroller, information obtained from the pre- and post-mandatory collection rate determinations conducted by the Comptroller and the OCA CIP Audit Department, and conviction (including deferred adjudications and deferred dispositions) statistics reported to OCA by the courts or clerks. Although Harris County has received a waiver from implementing OCA’s CIP, the collection program for the county-level and district courts has implemented OCA’s CIP requirements. Therefore, the collections for those courts (40 percent of the total county court collections) are included in the estimated additional revenue.

Inmate/Parolee Collections

In 1995, section 501.014(e) of the Texas Government Code was enacted to provide a simplified way to withdraw funds from an offender’s Inmate Account (commissary account) to pay for the expenses listed in the statute, as explained by the OCA. These expenses include child support, health care costs, court costs, fees, fines and restitution. Walker and Kerr counties pioneered the use of “Orders to Withdraw Funds from Inmates’ Accounts” to pay court costs, fees and fines. Since then, the practice of collecting from Inmate Accounts has been widely adopted.

During 2006-2007, litigation ensued over the process used to withdraw funds for the payment of criminal court costs, fees, fines and restitution. During that time period, the use of Orders to Withdraw Funds was stopped by the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ) due to the litigation. The matter was finally resolved when the Court of Criminal Appeals determined in Johnson v. The Tenth Court of Appeals at Waco, 280 S.W.3d 866 (Tex. Crim. App. 2008), that the withdrawal of funds was a civil matter. The Supreme Court in Harrell v. State, 286 SW3d 315 (Tex. 2009) issued an opinion affirming the process of withdrawal by direct court order under section 501.014 of the Texas Government Code, without the necessity of a hearing prior to the withdrawal.

Detailed instructions regarding the implementation of the Inmate Trust Fund Collection Program and contact information are available on the Texas Judicial Branch website at http://www.txcourts.gov/cip-tech-support/program-management/withdrawing-funds-from-inmate-accounts.aspx.

In brief, the stages include:

- Step One: Establish Contact with TDCJ

- Step Two: Notify the Offender

- Step Three: Send Order to Withdraw Funds and Judgment to TDCJ

- Step Four: Confirm the Transaction

In addition, the following important questions are answered in detail on the website:

- How much will be withdrawn from an offender’s Inmate Account?

- If an offender is convicted in multiple cases and there are, as a result, separate judgments, is a separate withdrawal order required for each case?

- Where does TDCJ send the checks?

- Does the clerk need to send a copy of the original judgment with a new Order to Withdraw Funds when an offender is sent back to prison after his/her parole has been revoked?

- Why did I receive one more payment when I sent an email to stop withdrawals?

- Why did I receive a withdrawal from an offender for less than $1.00?

- Can this process be used to withdraw funds from an offender’s local jail account?

In May 2014, Burnet County was recognized by the Governmental Collectors Association of Texas with the Most Innovative Program Award for taking the initiative to implement the TDCJ Inmate Trust Program.

Outsourcing Option

Another tool made available by the Texas Legislature is the authority of counties to assess a 30 percent fee on a delinquent fine or fee when contracting with a private attorney or public vendor to improve collection of balances more than 60 days past due.

When it comes to outsourcing collections, Scurry County Pct. 2 Justice of the Peace Ricki R. Webb points to manpower.

Scurry County hired Perdue Brandon Fielder Collins and Mott‚ LLP, to collect delinquent accounts for Webb’s precinct in 2005.

“With outsourcing, we don’t have to use all of our time and manpower trying to collect,” Webb emphasized. Rather, the collections firm searches for new addresses, sends out all the collection letters, and does all of the legwork to help the precinct prepare for warrant roundups, all the while significantly increasing Scurry County’s collection rate.

Judge Ginny Phifer took office as Delta County’s Justice of the Peace in January 2015; she had spent the previous 30 years working as a justice chief court clerk.

“After taking office and reviewing records, I became aware of the substantial amount of outstanding delinquent fines in this court,” Phifer detailed, “and I saw that a collection agency had never been implemented,” The court Phifer had served the previous 16 years used Graves Humphries Stahl, Ltd. (GHS); Phifer took action, and the county signed on GHS in October 2015.

Being a very small county with limited resources available, outsourcing not only allows the court’s one clerk to focus more on core activities, but also reduces overhead while “providing cost and efficiency savings that allow us to keep office expenses down to a minimal,” Phifer elaborated.

“Every business will have a collection issue at some point,” noted Medina County Pct. 4 Justice of the Peace Phil L. Montgomery. “The primary benefit of having a collection agency is that county employees can concentrate on the court and clients needing immediate assistance with either walk-in or by phone.”

Medina County contracted with McCreary, Veselka, Bragg & Allen, P.C., in 2006 to pursue delinquent fines and fees.

“Past due accounts can be time consuming and very hard to collect,” Montgomery observed. “Collection agencies not only have the technology, but the training skills and experience to follow up. One of the principal benefits of outside collections is doing the job properly and efficiently. This saves the county time by having them process delinquent accounts.”

McLennan County Precinct 3 Justice of the Peace David Pareya has been serving as judge for 40 years. In fact, Pareya and his clerk developed the first software used by a collection agency to assist the McLennan County courts.

When the Texas Department of Public Safety did away with the Warrant Data Bank, this meant a statewide mechanism to executing pending warrants on citations that were overdue in court no longer existed.

“We did not have the manpower on the local level to serve delinquent warrants on delinquent cases,” Pareya explained.

The McLennan County Pct. 3 Justice of the Peace Court contracted with Linebarger Goggan Blair & Sampson, LLP, said McLennan County Commissioner Kelly Snell.

“We have had great success with the firm’s assistance in disposing of our delinquent cases” Pareya maintained, “thus relieving the courts and defendants of going through the in-court proceedings.

“I would highly recommend that any official, with regard to collections of delinquent fines and fees, do some intensive research with all of the different entities that are available and see which ones fit the justice court’s needs,” Pareya concluded.