By Julie Anderson, Editor

Truth be told, this was never in the plan. His childhood dreams did not include wings, propellers or fatigues. Rather, he had his sights set on the law…and then timing came into play.

Truth be told, this was never in the plan. His childhood dreams did not include wings, propellers or fatigues. Rather, he had his sights set on the law…and then timing came into play.

John Firth graduated from the University of Redlands in Redlands, Calif., in 1968; he was accepted to law school and scheduled to start in the fall. However, in late July 1968 he received a letter from the U.S. Military Draft Board; Firth lost his college deferment and was ordered to report for his military physical examination.

If you had told this soon-to-be law student how his life would unfold from this point forward, he never would have believed you…

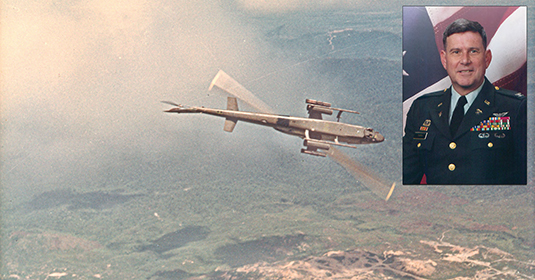

How he would log 1,200 flying hours as pilot of the Cobra attack helicopter, navigating the skies and taking fire over Vietnam.

How he would lose a fellow pilot and attend his funeral some 39 years later when that friend was finally brought home and laid to rest.

How he would serve in not one war, but two, leading 1,400 soldiers in Desert Storm. How he would lose three soldiers from his battalion, and how he would be the one to call parents and loved ones to tell them their sons had died on the battlefield in Iraq.

Or how he would remain on active duty in the U.S. Army for 31 years, and retire only because he had to.

“It was never part of the plan,” John Firth acknowledged, “but just a willingness to serve our great country.”

From the Schoolroom

to the Sky

Upon passing his physical examination, Firth was directed to an Army reception station for movement to Fort Ord., Calif., for basic training and advanced infantry training. While it wasn’t yet official, Firth knew exactly where he was going.

“I had been drafted shortly after the largest battle fought by American forces thus far in Vietnam, the Tet Offensive,” he recalled. Several of his high school friends had already been killed in Vietnam, “and certainly there was apprehension on my part,” Firth remembered.

It was no secret that some had been successful at avoiding the draft, yet Firth had never considered that option.

“It was certainly a diversion from my personal plans,” he acknowledged. “But it was obvious that the country needed the support of our men and women in uniform.

“The bottom line: I felt I had a personal responsibility to do my part. I also wanted to honor those who had already given their lives in the Vietnam War.”

Once again, timing came into play; because Firth had graduated from college, he was offered the opportunity to attend Infantry Officer Candidate School (OCS) in Fort Benning, Ga.

“If I was going to make a contribution, I felt I could make the best contribution in a leadership role,” Firth shared. “Since the Vietnam War depended to a large degree on helicopter support, while in OCS I was offered the chance to go to Army Flight School en route to Vietnam to become a pilot.”

Firth started Army Flight School at Fort Walters in Mineral Wells in early 1970 and graduated from advanced pilot training in Fort Rucker, Ala., with one last stop at Hunter Army Airfield in February of 1971 for pilot training in the Army’s advanced attack helicopter, the Cobra.

In-Country

1st Lt. John Firth arrived in Vietnam in March 1971, the same day as 1st Lt. Paul Magers of Billings, Mont. The pair had been in the same OCS class and flight school class, and both were assigned to the 101st Aviation Group as pilots of the AH-1 Cobra.

Most of Firth’s tour was spent in the northern part of South Vietnam where his mission was threefold: providing aerial cover to protect landing zones; supporting U.S. Army Special Forces operations in Vietnam and Laos; and providing aerial protection for medical evacuation missions.

During his yearlong tour, Firth’s company lost six Cobra pilots to enemy fire; within his Aviation Group, Firth lost his friend, Lt. Paul Magers. On June l, 1971, Magers and his gunner, Chief Warrant Officer 2 Donald L. Wann of Shawnee, Okla., were flying their Cobra during an emergency rescue of an Army Ranger team in Quang Tri, according to the U.S. Department of Defense.

After the Rangers were delivered to safety, Magers and Wann were ordered to destroy claymore mines that had been left behind in the landing zone. During this mission, ground fire hit the Cobra, which crashed and exploded; the Cobra’s ordnance detonated, ripping the aircraft apart. A ground search was deemed impossible, as enemy soldiers were in the area.

In March 2010, teams who specialize in returning the remains of military personnel identified the remains of the two soldiers, and in August of 2010, Magers was buried in Yellowstone County Veterans Cemetery in Laurel, Mont., with full military honors. John Firth attended the funeral.

“The toughest part was, he married just before leaving for Vietnam,” Firth conveyed with tears in his voice, “and he didn’t make it back.” Magers was listed as MIA (missing in action) for 10 years before the Army changed his status to KIA (killed in action).

“For 25 years, his wife never gave up hope that they would find Paul,” Firth shared, “but she died of cancer before they found him.” As Firth witnessed firsthand, Magers’ mother received the flag that draped her son’s casket.

Firth remained in Vietnam for some nine months following Magers’ death, logging 1,200 flying hours. Army regulations precluded pilots from more than 140 hours in any 30-day period, and Firth was “grounded” on several occasions in order to remain in that mandated window.

On Dec. 23, 1971, Firth piloted one of his most challenging missions. His Cobra was tasked with supporting the evacuation of soldiers out of Khe Sahn, which overlooked a major North Vietnam infiltration route in the A Shau Valley.

“While taking very heavy enemy fire, we were able to go in and protect the ‘lift’ helicopters that were transporting the soldiers,” Firth detailed. He made several passes, and both the Cobra he was piloting and the helicopter he was protecting were hit, with several wounded in the transport copter. Firth was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross (with valor) for this mission. The Distinguished Flying Cross recognizes a soldier “who distinguishes himself or herself in support of operations by heroism or extraordinary achievement while participating in an aerial flight.”

A Military Career

Firth returned from Vietnam in February 1972 and remained in the U.S. Army with assignments at Fort Benning, Ga., and Fort McPherson, Ga. His service as Battalion Commander in the First Cavalry Division at Fort Hood included deployment to the first Gulf War, Operation Desert Storm, in 1990. Firth’s assignment as Staff Officer at U.S. Central Command at McDill AFB, Fla., included deployment to combat operations in Somalia. Firth also served as Staff Officer at U.S. Forces Command in Korea, and Director of the Department of Defense Operational Research and Resource Analysis Agency in Richmond, Va.

Because he was not a general officer, Firth, a full colonel, was subject to mandatory retirement in the year 2000 after 30 years.

“It took me 11 months to go through basic, infantry training, and officer school,” Firth recounted. “Then I stayed for 30 more years. I really did not want to leave the Army,” he emphasized. “I stayed in for every day I could.”

Civilian Service

Upon his military retirement, Firth returned to Fort Hood as a civilian, hired by the Army as a project officer. The next year was marked by 9/11, and Firth’s duties included medical communications training and support for combat troops in Iraq and Afghanistan.

On June 4, 2007, Coryell County Judge Riley Simpson passed away, and Firth was approached by Coryell County Commissioner Jack Wall and asked to consider an appointment.

“He just stood out,” the Commissioner described. “He was very knowledgeable. He was an organizer and a manager for the Army. We could see that.”

In addition, Firth had a connection with Fort Hood, two-thirds of which is located in Coryell County, with the remaining third in Bell County.

Firth’s connections to Fort Hood “have really helped fill in some gaps,” Wall noted.

“He’s not a politician,” the Commissioner summarized. “He’s just a hard-working judge. Judge Firth is very humble and a great patriot. We need more like him.”

Following his appointment, Firth won a special election, and then won another full term; he is currently running unopposed for a second full term.

“I look at serving the citizens of Coryell County as a different kind of public service,” Firth declared, “and it is extremely rewarding.”

For Such a Time as This

Coryell County has the highest per capita number of veterans of any county in the State of Texas; the same applies to the number of Purple Heart recipients and number of disabled veteran tags issued.

As a veteran of two wars, one in which he was looked upon with disdain, and another where his country viewed him was a hero, Firth has a unique perspective on the needs of returning veterans and the importance of reintegration.

Soldiers who served in Vietnam were looked down upon “because we had been involved in contributing to a war that the vast majority of the country didn’t support,” Firth expressed, regardless of the fact that so many soldiers had no choice in the matter.

Firth has seen firsthand how some Vietnam veterans have “framed the rest of their life” on their experience in Vietnam and their dismal homecoming, with some ending up homeless or dependent on drugs.

“How do you ever give someone back a life?” he asked.

When Firth returned from Desert Storm, he and his fellow soldiers were treated as heroes and honored in a ticker tape parade in New York City.

“They appreciated us, and this really gave us a great sense of pride and satisfaction,” Firth shared. Thankfully, appreciation is finally being expressed to those of the Vietnam era, as well.

“Many in our country have really come to grips with the challenges of the Vietnam War and are able to separate their view on the war from the soldiers in the war, honoring them and thanking them for their service,” Firth imparted, a trend he hopes will continue.

For example, in late March, Gov. Rick Perry dedicated a new Vietnam Veterans Monument on the grounds of the Texas Capitol at a special event coinciding with the 41st anniversary of the last U.S. troops leaving South Vietnam.

“We still owe it to those we never really helped,” Firth maintained. “For those from Vietnam, we need to catch up and make sure we are fulfilling our responsibility.”

Communities must continue to serve combat veterans of all wars, especially those with mental health issues, Firth emphasized, “and as more and more troops are returning home from Afghanistan, the need for increased services and attention to reintegration is clear.”

Coryell County is answering the call in several ways. First, in September 2013, Coryell County received a grant from the Texas Indigent Defense Commission in the amount of $93,525 for the initiation of a new adult indigent defense program. According to the Coryell County Mental Health Defense Contract Policy & Plan of Operation, “If there is any question of priority of work or need, those receiving the highest priority of support under this MHDC program will be 1) combat veterans currently under Veterans Administration or Central Counties MHMR Services treatment with TBI or PTSD, 2) combat veterans with other mental health diagnosis, 3) non-combat veterans with mental health diagnosis, and 4) other indigent defendants with mental health diagnosis.”

Earlier this year, the Coryell County Commissioners Court passed two resolutions seeking help from the State of Texas to provide better mental health care to those in Central Texas, including veterans.

One resolution called upon the Texas Health and Human Services Department to increase the capacity of mental health care services in the six-county Regional Healthcare Partnership Area No. 16. The request is part of the Medicaid 1115 Waiver grant under which the county has already opened an eight-bed mental health crisis center in a renovated wing of the MHMR building in Gatesville. A second phase of the grant would provide operational funds for a new crisis respite center in Copperas Cove.

The second resolution urges the state to fund “results-oriented, evidence-based, proven treatment including Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy” for returning veterans who suffer from the “signature wounds” of Iraq and Afghanistan – traumatic brain injury and post-traumatic stress disorder. (See resolution, page 21.)

“I am so committed to helping veterans with mental health issues,” Firth asserted. “We are doing everything we can for them.”

Heartbreaking Reminder

Just days after sharing his story with County Progress, the eyes of the nation turned to Fort Hood once again in the wake of a tragic shooting; as of press time, investigators were trying to determine whether behavioral and mental health issues were contributing factors.

Both the 2009 tragedy at Fort Hood and the recent shooting on April 2 occurred within Coryell County, Firth observed, and “our hearts bleed again for the entire Fort Hood community.”