The Problem of Roadway Departures

When drivers leave the roadway, people often die or suffer serious injuries. The problem is not limited only to the nation’s highways. It is a problem of particular concern for “off-system” roadways in rural areas. In Texas, “on-system” generally refers to roads administered by TxDOT (federal/state highways and FM highways), so “off-system” rural roads are almost exclusively county roads.

Curves on rural roadways present particular problems. TxDOT’s Crash Records Information System (CRIS) reported that in 2011 rural roads of all types showed a high share of fatalities, accounting for 57 percent of fatalities and 32 percent of serious injuries. Of all fatal crashes, 54 percent involved roadway departures; on average the crash rate for curves is about three times higher than on straight road segments. When vehicles leave the road on curves, it is serious; more than 70 percent of such crashes result in fatalities due to a vehicle hitting a fixed object or overturning. (1)

Traffic Safety Duties

Based on court interpretations of the 1970 Texas Tort Claims Act, roadway officials have some responsibility for roadway safety. Drivers share in that responsibility, meaning officials cannot be held responsible for absolute safety. Courts have generally held public officials responsible to provide “reasonably safe” roadways. (2)

A roadway can be considered “reasonably safe” when it is adequate for prudent drivers to use without undue risk of harm; that is, the driver is behaving as most drivers would behave under similar circumstances, in general compliance with roadway, traffic, and weather conditions. Basically, officials have a duty to make roadways safe, or to warn drivers to help them safely negotiate the roadway. (3)

Understanding Suitable Actions

To improve roadway safety, officials need to:

- Understand the crash factors.

- Know the characteristics of their roads.

- Learn how these characteristics can hamper good driver performance.

- Act to better help drivers adjust for difficult road conditions.

Several factors contribute to traffic crashes: drivers, vehicle(s), weather conditions, and roadway features.

All have potential effects, but all may not have affected a particular crash; vehicle malfunction is one example. Roadway officials only control physical roadway features, although they can influence driver actions through speed limits and advisory information.

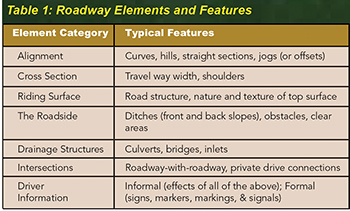

Roadway features can be categorized as outlined in Table 1. Alignment, cross section, riding surface, the roadside, and driver information affect safety along the full length of any roadway. By contrast, drainage structures and intersections are point locations.

Working in concert, they all affect driver behavior to some extent, albeit different effects on different drivers. For example, a narrow road with a poor riding surface will cause all drivers to operate slower than they would on a better road, but all drivers will not slow to the same speed.

Off-System Road Characteristics

Texas county roads can “surprise” unfamiliar drivers by presenting unexpected conditions inconsistent with their usual experience on highways and city streets. Few county roads in Texas have been “engineered” (designed to satisfy specific speed characteristics). Most are little more than early wagon routes, explaining the narrow right of way (ROW) and the sharp crests at hills. Most follow early property lines, explaining why straight sections are coupled with tight bends around property corners. Also, rivers, creeks, and roadside stormflow often result in drainage features that can further complicate traffic safety.

How Roads Can Hamper Driver Performance

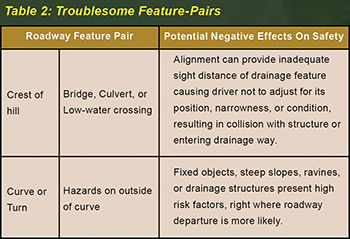

Roadway features can contribute to traffic safety difficulties, particularly when their position presents a combined effect. Table 2 lists two example pairs of features (feature-pairs) that are fairly common, along with a description of their potential effects. Many other pairs can also be of concern. Vegetation in or near the ROW can further aggravate the combined negative effects.

Acting To Meet Driver Information Needs

Drivers depend on a steady stream of information for making good second-by-second decisions. They react to both informal and formal input. Informal information is provided by the driving environment: tree lines, buildings, and the roadway itself, to list a few. Formal information is provided by design: signs, markers, pavement markings and signals. Due to limited budgets and the nature of their roads, most Texas counties must depend solely on signs and markers. Nevertheless, these can help offset the potential negative effects of difficult feature-pairs.

Properly deployed and maintained, signs and markers warn drivers in advance of a condition so they can adjust, usually with reduced speed and greater vigilance. Proper and consistent use of signs and markers on a system-wide basis can reduce system-wide crashes.

The experience of Mendocino County, Calif., offers one example. The county reduced county-wide crashes by 42 percent over a six-year period by systematically correcting or adding signs and markers by properly placing the right signs and markers at the right locations along all their roadways. (4)

Making a Difference

County officials can make a difference in traffic fatalities and injuries. They have responsibility for thousands of miles of roads, and they have a legal duty to do what they can to make them reasonably safe. While they cannot correct all of the feature-pairs that might contribute to traffic crashes, they can take steps to meet their minimum duty…warn drivers! Success depends on four actions:

1. Build the Right Attitudes.

A traffic safety improvement attitude should be part of the county road culture. From leadership through work crews, emphasis should be placed on the safety value of all maintenance and improvement actions including vegetation control, placement and maintenance of signs and markers, and travel way and drainage maintenance. For best results, attitudes need to reflect the idea that all actions are taken to improving road safety, at least in part.

2. Treat the Worst First.

No jurisdiction can address all potential roadway safety issues at once. One approach is to identify roadway feature-pairs presenting the poorest safety situations. Examples include:

curves/turns having unusually hazardous situations along their outside;

sharp turns approached by long, straight road segments;

curves/turns hidden from the driver’s view by the crest of a hill; and

curves/turns that hide drainage structures from adequate view by the driver.

After these are identified, it is important to correctly post the right warning signs. Officials should then deal with areas presenting lesser problems. Doing nothing is an option that may be difficult to defend.

3. Document Actions Taken.

Deliberate and systematic efforts to address traffic safety are important. This helps discharge the public duty, even if actions cannot be taken quickly. Efforts should be carefully documented. Documentation must include how hazardous areas are identified and prioritized, what actions were taken at specific locations, when they were done, and who did the work. It is important to document why a specific action was chosen from possible solutions and how resources were allocated among competing locations. Good practices can go far toward making roads safer and toward defending a county’s actions. Good documentation and a system for storing and retrieving are fundamental to wisely exercising the roadway safety duty.

4. Get Help.

Technical assistance, technical information, and training are available from the Texas LTAP Center at TEEX. Give us a call, or email your questions to Bill.Lowery@teex.tamu.edu. County officials may also be able to get help from the TxDOT office serving their area.

References:

(1) Crash Records Information System, www.dot.state.tx.us (Crash Records, 2011).

(2) Risk Management to Reduce Roadway Tort Liability, TEEX Course, 2002

(3) Transportation Safety and Tort Liability, TEEX Course, 2009.

(4) Road System Traffic Safety Review Showcase: Report by Mendocino County DOT, Stephen Ford, 2004

Originally published in Lone Star Roads Issue 3, 2012. Reprinted with permission.