By Julie Anderson

Editor

The statistics are staggering and startling. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), overdose deaths involving prescription opioids were five times higher in 2016 than 1999, and sales of these prescription drugs have quadrupled.

“Opioid prescribing continues to fuel the epidemic,” the CDC states. “Today, 40 percent of all U.S. opioid overdose deaths involve a prescription opioid. In 2016, more than 46 people died every day from overdoses involving prescription opioids.”

The CDC also points out that overdose is not the only risk related to prescription opioids. Misuse, abuse, and opioid use disorder (addiction) are also potential dangers, https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/data/overdose.html.

- In 2014, almost 2 million Americans abused or were dependent on prescription opioids.

- As many as 1 in 4 people who receive prescription opioids long term for noncancer pain in primary care settings struggles with addiction.

- Every day, over 1,000 people are treated in emergency departments for misusing prescription opioids.

The Office of National Drug Control Policy reports that in 2016, more than 11.5 million Americans ages 12 and older reported misuse of prescription opioids in the past year.

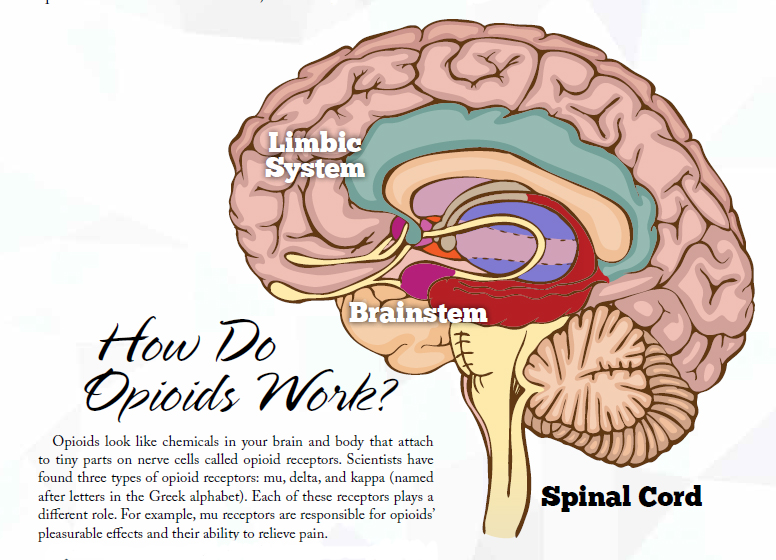

According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, opioids bind to and activate opioid receptors on cells located in many areas of the brain, spinal cord, and other organs in the body, especially those involved in feelings of pain and pleasure. When opioids attach to these receptors, they block pain signals sent from the brain to the body and release large amounts of dopamine throughout the body. This release can strongly reinforce the act of taking the drug, making the user want to repeat the experience. For more information, see the related box, What are Prescription Opioids? on page 26.

The tragedy behind the number of deaths and addictions continues to surface as more and more families take to the air waves and social media and visit support groups and schools to tell their stories in the name of prevention. Parents are losing sons and daughters, siblings are growing up without their brothers and sisters, children are being placed in foster homes as their parents undergo court-ordered treatment, and newborns are being diagnosed with opioid withdrawal after birth, known as neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS). Many of these sad scenarios involve emergency response, health care, indigent health care, social services and law enforcement, all of which involve local government.

For several years entities in other states have been taking legal action in an attempt to hold various parties including pharmaceutical companies, marketers and distributors responsible for the epidemic and recoup costs. Some liken the effort to the historic settlement negotiated with tobacco companies in the summer of 1998. With regard to Texas counties, tobacco companies agreed to create a $2.275 billion fund for the benefit of “all hospital districts, other local political subdivisions owning and maintaining public hospitals, and counties of the State of Texas responsible for providing indigent care to the general public.”

Counties Taking Legal Action

Upshur County was the first Texas county to file suit against opioid makers, taking action in October 2017 citing the impact on indigent health care costs and inmate care.

“By pursuing cases against the opioid drug industry, counties have a chance to recover some of the taxpayer money they have spent and continue to spend to combat the high cost of opioid addiction, overdose, and diversion in their communities,” stated Jeffrey Simon, attorney and co-founder of Simon Greenstone Panatier Bartlett, P.C., the firm representing Upshur County. “Most successful methods to treat opioid addiction cost a great deal of money, and often those costs fall upon counties. A prime example is when an opioid addict is arrested and put into jail.”

Simon Greenstone has also filed lawsuits on behalf of Bowie, Cherokee, Hopkins, Lamar, Morris, Red River, Rusk and Titus counties.

The McLennan County Commissioners Court retained counsel and filed a lawsuit against opioid manufacturers and distributors in October 2017.

“We are trying to recoup some of the cost,” explained McLennan County Judge Scott Felton. McLennan County is a medium-size county, much larger than surrounding counties.

“Their medical facilities are not as advanced as ours; therefore, we have a lot of opiate abusers who cross county lines,” Felton continued.

Harris County filed its petition in December 2017, noting that “Texas counties have found themselves to be innocent participants in the battle against opioids and their crushing financial effect on our county.”

The suit notes that the county provides services on behalf of its residents “including but not limited to, services for families and children, public health, public assistance, law enforcement, and social services, as well as medical and prescription benefits that the county provides to its employees and retirees.”

As explained in its lawsuit filed on Jan. 8, 2018, Dallas County “provides a wide range of services on behalf of its residents, including services for families and children, public health, public assistance, law enforcement and emergency care.”

By filing suit, Dallas County hopes to “hold the responsible drug companies financially accountable for their significant role in creating this epidemic in Dallas County and, through any financial recovery in the case, to provide more and better opioid addiction treatment, overdose treatment, neonatal care for opioid-addicted newborns, foster care for the children of opioid-addicted parents, and educational programs to prevent the spread of opioid overuse,” shared Ruby Blum, health policy adviser to Dallas County Judge Clay Jenkins.

“The ongoing opioid epidemic is devastating Texas communities and draining significant public resources,” declared Mark Lanier, attorney and founder of The Lanier Law Firm, one of the firms representing Dallas County. “Texas counties are ground zero for this fight and the nuisance it creates in our communities.

“Pursuing litigation provides an avenue for Texas counties to recoup the significant resources drained from their budgets as well as a path to abate this public nuisance through injunctive relief,” observed Lanier, whose firm also represents Tarrant and Travis counties, among others.

“This is not just about collecting money damages,” Lanier continued. “It represents an avenue to try and fix this crisis going forward.”

In early December 2017, the U.S. Judicial Panel on Multidistrict Litigation (MDL) ordered that all federal opioid lawsuits be sent to U.S. District Judge Dan Polster of the Northern District of Ohio.

When an MDL is created, lawsuits that have been filed in federal courthouses across the country are consolidated and transferred to a single federal court. The opiate suit is officially known as the National Prescription Opiate Litigation – MDL No. 2804. In January, a plaintiffs’ executive committee was appointed to assist and advise lead counsel “in the massive undertaking of coordinating and conducting pre-trial proceedings.” Mark Lanier of The Lanier Law Firm was selected for this committee.

While some Texas counties have filed lawsuits in federal court, others have filed in state courts.

Evolving Opioid Use

According to the Upshur County lawsuit, opioids were tightly regulated for short-term acute pain treatment and to ease end-of-life suffering until the manufacturers made a push in the late 1990s to encourage doctors to expand prescribing painkillers.

“Relying on now-debunked studies and the assurances of key medical opinion leaders, primary care doctors were inundated with a message that opioids were a safe, non-addictive means to treat even moderate chronic pain on a long-term basis,” the lawsuit states.

Other county suits state that the defendants downplayed the serious risk of addiction; promoted and exaggerated the concept of “pseudoaddiction” thereby advocating that the signs of addiction should be treated with more opioids; exaggerated the effectiveness of screening tools in preventing addiction; claimed that opioid dependence and withdrawal are easily managed; denied the risks of higher opioid dosages; and exaggerated the effectiveness of “abuse-deterrent” opioid formulations to prevent abuse and addiction.

Pharmaceutical companies are vehemently denying the allegations, pointing to policies that deter pain killer abuse. Other defendants are also denying the claims and have stated they are eager to defend themselves in court.

“Opioid prescription medications are highly addictive, but have legitimate medical use in limited circumstances,” noted Dallas County Judge Clay Jenkins. “This is why they have long been Schedule II controlled drugs.

“Most doctors who prescribe opioids are good doctors who practice safe medicine in prescribing opioids to patients who legitimately benefit from them in conservative use,” Jenkins continued. The Dallas lawsuit “will not hinder the prescribing and use of opioid pain medications for therapeutic purposes. But too many opioids are being consumed in Dallas County because certain drug companies have aggressively promoted opioids as less addictive and safer for perpetual use than they really are. And some distribution companies have knowingly turned a blind eye at suspicious prescription patterns, and they need to stop. This lawsuit is intended to bring common sense and restore public health by reducing the glut of opioids in this county and the misery that glut causes.”

As of press time, none of these cases had proceeded to trial, and counties were still determining exact damages. Both officials and litigators have acknowledged that these types of cases often take long, winding paths and could take years to resolve.

Litigation Considerations

For those counties who may be contacted by firms to consider litigation, Jim Allison, general counsel to the County Judges and Commissioners Association of Texas, offered perspective and suggested questions:

Since recovery in these cases is not certain and litigation costs will be large, counties usually seek representation on a contingent fee basis. This means that the law firm provides representation and covers all expenses for a percentage of any recovery. When considering such representation, the Commissioners Court should carefully evaluate the proposed legal services agreement, Allison advised. Some standard questions include the following:

- What experience and success has the law firm demonstrated in these types of cases in the past? Did those include representing governmental entities? Who will be responsible for communication with the county?

- What is the financial capacity of the law firm to provide representation over an extended period while covering the expenses, including fees for expert witnesses? Has the firm prepared a litigation budget and estimated timeline?

- Has the law firm been retained by other governmental entities in this matter? How will any recovery be divided among the entities?

- Will the law firm affiliate with other law firms representing other plaintiffs in this matter? How will expenses, fees and recovery be divided among the law firms?

- Where will this lawsuit be filed? State court or federal court? Why?

- If in federal court, is the firm affiliated with a firm that is part of the MDL?

- Does the law firm intend to join this suit into a class action? If so, why?

The proposed legal services agreement should be reviewed by an attorney for the county to ensure that it is a true contingent fee contract, Allison said. In the past, some firms have attempted to obligate counties to pay litigation expenses regardless of the outcome. Some firms have attempted to include normal operating costs as litigation expenses, increasing their share of any recovery.

There is no need to rush these decisions, Allison observed. When in doubt, consider proposals from several firms.