The current drought in Texas is the most intense one-year drought since the state began keeping rainfall records in 1895 and ranks among the five worst  droughts in the state overall. Today, all of Texas’ 254 counties are experiencing drought, most in the exceptional drought category. This has led to severe declines in aquifer and reservoir levels, compromising water supplies and delivery to several public water systems. It also has contributed to one of the worst wildfire seasons in Texas history. Texas has responded to more than 24,000 wildfires, which have burned more than 3.8 million acres and destroyed more than 7,000 homes and businesses.

droughts in the state overall. Today, all of Texas’ 254 counties are experiencing drought, most in the exceptional drought category. This has led to severe declines in aquifer and reservoir levels, compromising water supplies and delivery to several public water systems. It also has contributed to one of the worst wildfire seasons in Texas history. Texas has responded to more than 24,000 wildfires, which have burned more than 3.8 million acres and destroyed more than 7,000 homes and businesses.

A second year of drought in Texas is likely, according to state climatologist Dr. John Nielsen-Gammon, which would result in further drawdown of water supplies in 2012 and possibly beyond. The major drought of the 1950s, the “drought of record,” led the state to invest in infrastructure for water supply, but this infrastructure has not really been tested by a comparable drought with a substantially larger population.

Texas lacks adequate water to meet the needs of people, businesses, and agricultural enterprises, according to the 2012 State Water Plan recently approved by the Texas Water Development Board (TWDB) and submitted to the governor and Texas Legislature in January. According to the TWDB, if Texas does not implement the new projects or management strategies recommended in the plan, then the state is projected to need 8.3 million acre-feet of additional supply by 2060. An acre-foot of water is 325,851 gallons.

Texas lacks adequate water to meet the needs of people, businesses, and agricultural enterprises, according to the 2012 State Water Plan recently approved by the Texas Water Development Board (TWDB) and submitted to the governor and Texas Legislature in January. According to the TWDB, if Texas does not implement the new projects or management strategies recommended in the plan, then the state is projected to need 8.3 million acre-feet of additional supply by 2060. An acre-foot of water is 325,851 gallons.

If water supply needs are not met and current drought conditions approach the drought of record, Texas could lose about $11.9 billion in income annually and as much as $115.7 billion annually by 2060, with more than a million lost jobs, according to TWDB.

Texas AgriLife Extension Service has estimated that the cost of the drought to the state as of August 2011 was about $5.2 billion, due to the lower yield and loss of major crop commodities such as cotton, wheat, corn, hay, and grain sorghum, as well as higher the costs of caring for livestock.

On Oct. 1, 2011, Gov. Rick Perry renewed and extended a December 2010 disaster proclamation resulting from extreme fire danger to include the  effects of prolonged drought and extreme high temperatures. The proclamation directs that all necessary measures, both public and private, be implemented to ameliorate the effects of the drought, including suspending rules and regulations that may inhibit or prevent prompt response to the threat.

effects of prolonged drought and extreme high temperatures. The proclamation directs that all necessary measures, both public and private, be implemented to ameliorate the effects of the drought, including suspending rules and regulations that may inhibit or prevent prompt response to the threat.

In addition, many Senate and House interim study charges focus on the drought and ways to implement the State Water Plan and enhance existing water supply. State agencies have responded to the drought by continually monitoring the status of public water systems, responding to calls for enforcement of water rights, and seeking ways to find and fund new sources of water and conserve existing ones.

Public Water Systems

State agencies are monitoring public water systems to ensure adequate water supplies and to offer assistance when available water falls below a certain threshold.

TCEQ monitoring. The Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) monitors water systems and contacts them to determine their condition and the status of their drought contingency plans. The commission has sent letters to about 6,000 public water systems statewide encouraging them to implement contingency conservation plans.

According to TCEQ, as of Nov. 25, 2011, 964 public water systems had asked customers to follow outdoor water use restrictions. Of these, 320 had asked customers to follow a voluntary watering schedule and 644 had implemented mandatory water schedules, with 52 prohibiting all outside watering.

Emergency management. TCEQ is monitoring a targeted list of 11 public water systems with water supplies that either are unknown or are expected to last for fewer than 180 days. TCEQ has offered these systems financial, managerial, and technical help, including identifying alternative water sources and possible funding for those sources and coordinating emergency drinking water planning.

The Emergency Drinking Water Task Force – created and chaired by the Texas Department of Emergency Management (TDEM) with members from TDEM, TWDB, and TCEQ, which has operational responsibility – meets weekly to track systems identified by TCEQ as having 180 days or fewer of potable water. Once such a water supply is confirmed, the task force will support the system’s attempts to obtain a new supply by providing technical assistance and help with locating funding or with grant or loan applications. Efforts could include:

moving the water intake line, if possible, into a deeper section of the resource pool; establishing an interconnection with a nearby water system; re-establishing a previously used well; drilling a new well; establishing a new source of surface water via pipeline; hauling treated water from another public water system; or hauling untreated water for insertion into the local treatment system.

If efforts by the local water system will not prevent depletion of its water source, requests for state assistance are directed through the established emergency management system. This begins with the city, works up to the county, and ends with the state, the last resort being to have TDEM ship in potable water.

As an example of severe local water shortage, Mayor Jackie Levingston of the city of Groesbeck declared a local state of emergency in October 2011 due to an estimated 30-day supply of water and indicated in a letter to the governor a need for further state aid. Fort Parker Lake, the city’s water source, was expected to reach a critical level by Nov. 21, when the city no longer would be able to pump water from it. However, rainfall increased the lake level, providing an estimate of another 90 days of water supply.

Following the mayor’s request, under the existing statewide disaster proclamation, TDEM, TCEQ, Texas Parks and Wildlife Department (TPWD), the Texas Department of Transportation, and the city of Nacogdoches have helped Groesbeck secure a pipeline to pump water from a nearby quarry. The pipeline, completed on Dec. 1, is expected to provide an estimated six- to nine-month additional supply of water.

Representatives from city, state, and federal agencies and from local utilities recently attended a meeting in Groesbeck to address medium- and long-term plans to address the city’s potential water shortages. Options discussed included interconnecting with nearby utilities and developing groundwater wells. Funding solutions discussed included rate increases, temporary surcharges, and grants or loans from the Texas Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Drought Preparedness Plan

The State Drought Preparedness Council, created by the 76th Texas Legislature in 1999, is responsible for preparing and updating a comprehensive state drought preparedness plan separate from the State Water Plan for mitigating the effects of drought in the state. The plan outlines long- and short-term measures to prepare for and respond to drought, identifying drought triggers, and assigning responsibilities to agencies. It is continuously updated with input from all state agencies, federal partners, water utility systems, water authorities and other stakeholders. The council now is working to identify drought triggers for all 10 climactic regions of the state. Chaired by TDEM, the council includes representatives from several state agencies and a representative of groundwater management interests appointed by the governor.

Water Rights Enforcement

Since April 2011, TCEQ, which is charged with managing surface water rights and regulating public water systems, has received 14 “senior calls.” A senior call occurs when a water rights holder not receiving water to which the right holder is entitled calls on TCEQ to enforce the “prior appropriations” doctrine. The prior appropriations doctrine is used to manage surface water rights in Texas and gives superior rights to first users of the water. This often is described as “first in time, first in right.” The most senior water rights are served first during times of drought, but domestic and livestock uses are superior to any appropriated rights. Water rights are suspended or curtailed by priority date, with the most recently issued – or “junior” – priority users suspended before senior water rights in the area.

Senior calls to TCEQ seeking to enforce water rights have included those on surface water in the Brazos, Guadalupe, Colorado, Sabine, and Neches river basins. TCEQ has suspended or curtailed more than 1,200 water right permits in response to senior calls and has stopped issuing temporary water right permits in basins affected by these calls. According to TCEQ, any curtailment can significantly affect other users, so their response to senior calls has been measured. TCEQ field staff have enforced suspensions and curtailments through on-the-ground and aerial investigations and have monitored stream flow to help the agency make informed decisions on management of senior calls.

In order to protect public health and welfare, water rights with municipal uses or for power generation have not been suspended. TCEQ has advanced the stages of drought contingency plans in senior call areas, including requiring junior municipal water rights holders to implement mandatory restrictions to limit outdoor water use.

Suspending Surface Water Rights

TCEQ’s Sunset bill, House Bill 2694 by W. Smith, enacted by the 82nd Legislature during its 2011 regular session, allows the TCEQ executive director, by order and according to the priority of water rights established in the Water Code, to suspend or adjust rights during a drought or emergency shortage of water. Several factors must be considered before issuing such an order.

As required by HB 2694, TCEQ recently proposed rules to define “drought” and “emergency shortage of water” and to specify conditions and terms under which the executive director could suspend or adjust water rights during those times. TCEQ held a stakeholder meeting on August 11 to obtain public input. The close of the public comment period was Dec. 5, 2011. TCEQ will consider adopting the rules on April 11, 2012.

The proposed rules would allow the executive director to issue an order without notice to cut off or adjust water rights during a drought or emergency shortage of water. A hearing would be required to affirm, modify, or set aside the order. The rules require that notice of the hearing be given to all holders of water rights that were suspended or adjusted under the order. These orders could be issued for up to 180 days, with 90-day extensions.

The rules would require that the executive director base determinations on the prior appropriations doctrine but allow other factors to be considered, such as an affected water right holder’s efforts to develop and implement drought and conservation plans, prevent waste, and maximize beneficial uses.

State Water Plan

The State Water Plan is designed to meet water needs during times of drought. Its purpose is to ensure that cities, rural communities, farms, ranches, businesses, and industries have enough water during a repeat of the 1950s drought conditions. In Texas, each of 16 regional water planning groups is responsible for creating a 50-year regional plan and refining it every five years so conditions can be monitored and assumptions reassessed. TWDB develops the state plan, which includes policy recommendations to the Legislature, with information from regional plans. The official state plan is expected to be delivered to the Legislature in early 2012.

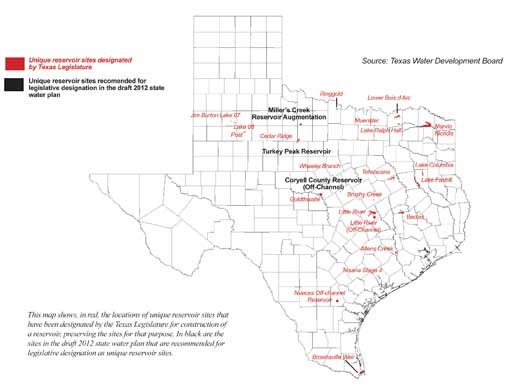

The 2012 State Water Plan includes the cost of water management strategies and estimates of state financial assistance required to implement them. It also details economic losses likely to occur if these water supply needs cannot be met. Regional water planning groups recommended water management strategies that would account for another 9 million acre-feet of water by 2060 if all strategies were implemented, including 562 unique water supply projects. About 34 percent of the water would come from conservation and reuse, about 17 percent from new major reservoirs, about 34 percent from other surface water supplies, and the remaining 15 percent from various other sources.

Dedicated Funding for Water Projects

Among TWDB’s recommendations to the Legislature to facilitate implementation of the 2012 State Water Plan is the development of a long-term, affordable, and sustainable method to provide financing assistance to implement water supply projects.

According to the TWDB, critical water shortages will increase over the next 50 years, requiring a long-term, reliable funding source to finance water and wastewater projects. The State Water Plan has identified projects intended to help avoid catastrophic conditions during a drought, but rising costs for local water providers, the capital-intensive investment required to implement large-scale projects, and the financial constraints on some communities necessitate a dedicated source of funding to help develop those projects. According to TWDB, the capital cost to design, build, or implement the recommended strategies and projects between now and 2060 will be $53 billion. Municipal water providers are expected to need nearly $27 billion in state financial assistance to implement these strategies.

General obligation bonds. On Nov. 8, 2011, voters approved a constitutional amendment (Proposition 2) with 51.42 percent of the vote to allow TWDB to issue, in addition to the bonds authorized by other provisions of the Texas Constitution, general obligation bonds for one or more accounts of the Texas Water Development Fund II (DFund II). The aggregate principal amount of the bonds outstanding at any time may not exceed $6 billion. According to TWDB, without the additional bond authority, TWDB would have been unable to provide the financing needed to meet the state’s water and wastewater needs through the next two-year state budget period.

Water implementation fee. During the 2011 regular session, Rep. Allan Ritter introduced House Bill 3273 and House Joint Resolution 138 to fund certain projects identified in the State Water Plan. The legislation would have established a state water implementation fee – a public water supply service connection fee that retail public utilities would have had to collect from each consumer. Both bills were reported favorably by the House Natural Resources Committee but never scheduled for floor debate.

Watermasters

Texas relies on the honor system in most parts of the state to protect water rights during a drought, but TCEQ has appointed two “watermasters” to oversee three areas and continuously monitor streamflows, reservoir levels, and water use. The Rio Grande watermaster coordinates releases from the Amistad and Falcon reservoir system. The South Texas watermaster serves the Nueces, San Antonio, Guadalupe, and Lavaca river basins, as well as their coastal basins, and serves the Concho River and its tributaries in the Colorado River basin.

TCEQ’s Sunset bill, House Bill 2694, requires the executive director to assess the need for watermaster programs at least every five years in basins where programs to oversee and continuously monitor streamflows, reservoir levels, and water use do not now exist. The commission recently approved the criteria, process, and schedule for watermaster program evaluation. The executive director will evaluate the Brazos, Brazos-Colorado Coastal, Colorado, and Colorado-Lavaca coastal basins in 2012. H – By Blaire D. Parker

This article was reprinted with permission from the House Research Organization, a nonpartisan department of the Texas House of Representatives that examines state issues and analyzes legislation being considered by the Texas Legislature. To view the report in full, go to http://www.hro.house.state.tx.us/pdf/interim/int82-1.pdf

The Texas Water Development Board’s 2012 State Water Plan is now available to the public at http://www.twdb.state.tx.us/wrpi/swp/swp.asp. The Texas Water Development Board is the state agency charged with collecting and disseminating water-related data, assisting with regional water supply planning, and preparing the State Water Plan for the development of the state’s water resources. The plan, updated every five years, was approved by the Board at its Dec. 15, 2011, meeting and was delivered to the governor and Texas Legislature Jan. 5.

The Texas Water Development Board’s 2012 State Water Plan is now available to the public at http://www.twdb.state.tx.us/wrpi/swp/swp.asp. The Texas Water Development Board is the state agency charged with collecting and disseminating water-related data, assisting with regional water supply planning, and preparing the State Water Plan for the development of the state’s water resources. The plan, updated every five years, was approved by the Board at its Dec. 15, 2011, meeting and was delivered to the governor and Texas Legislature Jan. 5.

The primary message of the 2012 State Water Plan is a simple one: In serious drought conditions, Texas does not and will not have enough water to meet the needs of its people, its businesses, and its agricultural enterprises. This plan presents the information regarding the recommended conservation and other types of water management strategies that would be necessary to meet the state’s needs in drought conditions, the cost of such strategies, and estimates of the state’s financial assistance that would be required to implement these strategies. The plan also presents the sobering news of the economic losses likely to occur if these water supply needs cannot be met. As the state continues to experience rapid growth and declining water supplies, implementation of the plan is crucial to ensure public health, safety, and welfare and economic development in the state.

The population of Texas is expected to increase 82 percent by 2060, and existing water supplies are expected to decrease 10 percent in the same time period. If the state does not implement new water supply projects or management strategies, Texans will not have enough existing water supplies to meet demand in times of drought. By 2060, the state is projected to need 8.3 million acre-feet of additional water supply per year in the event of a drought. Annual economic losses from not meeting water supply needs could result in a loss of $11.9 billion in income a year if current drought conditions persist, and as much as $115.7 billion annually by 2060, with over a million lost jobs. (See related story, page ?.)